The passing of the Legal Services Act marked the dawn of a new era – a move to liberalise the legal sector to open opportunities for innovation to benefit both legal teams and legal services providers.

In this report, we resurface the leading voices that called for change and pioneered the way; explore the impact on legal teams and cast an eye to what the future may hold.

Prefer a PDF? Click here

The Legal Services Act – then and now

On 6 October 2011, English legal history was made when Premier Property Lawyers – one of the country’s largest conveyancing businesses – became the first ever ABS.

It was perhaps less of a landmark than the authors of the Legal Services Act 2007 might have hoped, as it already had external investment. Firms regulated by the Council for Licensed Conveyancers had been able to do so for several years and were required to convert into ABSs. The company has since been bought by private equity, Palamon Capital Partners.

The way the Legal Services Act set up the regulatory regime, the individual regulators could each run their own ABS licensing system. So it was nearly six months later that the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) licensed its first ABS – Oxfordshire high street firm John Welch & Stammers, followed the next day by Co-operative Legal Services. Both are still going strong. Co-operative Legal Services was already a significant business at that time, but becoming an ABS allowed it to offer reserved legal activities. It has recently outlined an ambition to become a £100m business in the next five years (its turnover in 2021 was £39m).

Since then, around 1,500 ABSs have been licensed – mainly, but not exclusively, by the SRA. There are now law firms listed on the stock exchange (e.g DWF, Ince & Co), law firms bought by private equity (e.g. Fletchers by Sun Capital Partners, Stowe Family Law by Livingbridge), law firms run by local authorities, charities, universities and businesses, there are consolidators, multi-disciplinary practices with accountants, surveyors and even funeral directors, and many more besides.

A market ripe for liberalisation

The Act that paved the way for ABSs is often wrongly described as a deregulatory measure. It’s not, however – ABSs are subject to the same regulatory oversight as ‘traditional’ law firms. Rather, the main purpose of the Act was to liberalise the legal sector.

Professor Stephen Mayson, arguably the leading observer of the post-Legal Services Act world, says his expectations at the start were in line with Sir David Clementi, – whose government-commissioned report led to the Act – namely “shifting the market away from one that was dominated by traditional law firm partnerships and limited liability partnerships, and getting lawyers thinking differently about the structural opportunities that ought to be available to them.”

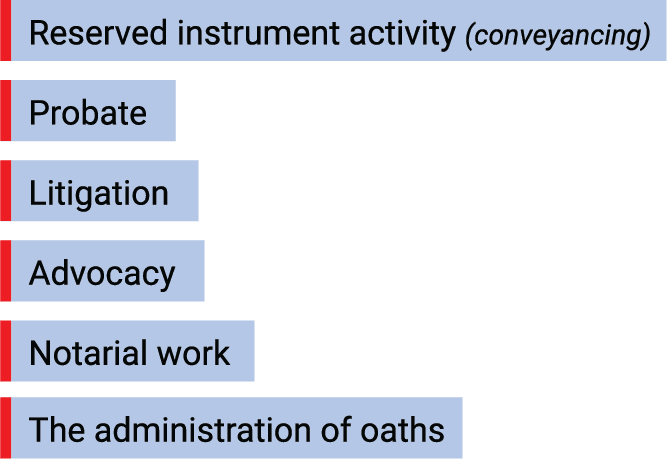

6 areas of E&W law are regulated

Legal regulation in England and Wales means that you only need to be a regulated lawyer to conduct six types of legal activity (the ‘reserved legal activities’):

“For me it was about making the opportunity available. It’s then whether or not people take it. Liberalisation was permissive rather than prescriptive.”

__

Professor Stephen Mayson

There is a perception that liberalisation has not taken off because, contrary to expectation at the time, ‘Tesco Law’ – shorthand for large consumer brands entering the legal market – did not materialise. But compare the market now to what it looked like a decade ago, and you will see it has changed significantly, and in fact several big names, particularly insurance companies, now offer legal services.

The market was ripe for new ways of operating – and there were some who were brave enough to lead the charge. In many cases, it took the Act to kickstart them, even though they did not need liberalisation to do what they wanted.

A hunger for fresh thinking

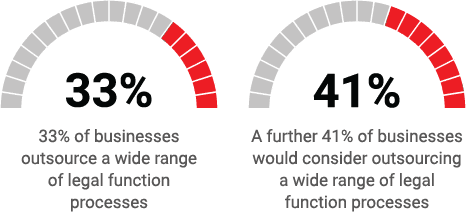

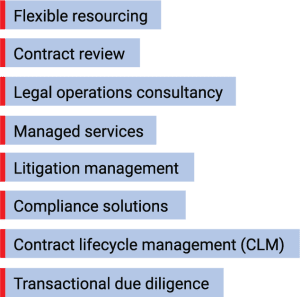

The rise of the alternative legal services providers (ALSPs) has in part come off the back of the wave of innovation that the Act unleashed – some ALSPs are regulated while others, often doing much the same work, are not.

1 in 10

law firms is an ABS

and SRA Statistics show the number of ABS licences continues to increase

The legal services market

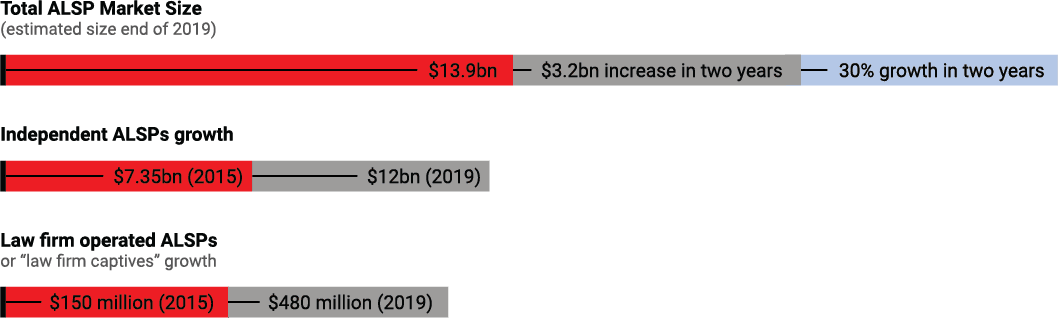

Thomson Reuters Report ‘Alternative Legal Service Providers 2021: Strong Growth, Mainstream Acceptance, and No

Longer an “Alternative”’ – a biennial examination of the ALSP market in the US, UK, Canada and Australia.

“Indeed, this could well be the tipping point for the ALSP market, as greater acceptance, more tech-tuned business acumen, and a wider array of service offerings is demonstrably transforming the ALSP market. Paving the way for rapid growth and expanded market share.”

__

Thomson Reuters ALSP Report 2021

In its The State of Legal Services 2020 report – published to mark a decade of independent regulation resulting from the 2007 Act – the Legal Services Board, the sector’s oversight regulator, said: “Our surveys suggest that ABSs are more innovative than traditional law firms. The Big Four accounting firms all hold ABS licenses, and their scale and multi-disciplinary approach holds the potential for disruption in the corporate market.”

Crispin Passmore has been at the forefront of delivering regulatory change, holding policy leadership roles first at the Legal Services Board and then the SRA. He finds the scale of progress made in the last decade overlooked by many. Yet, he also acknowledges that legal services provision has not changed that much for corporate clients.

So what significance, if any, has the liberalisation had for corporate legal teams?

%

of ABS have

introduced new services

vs 13% for non-ABS firms

Technology and Innovation in Legal

Services Report, SRA, July 2021

The Era of Choice

It was the ABS revolution which sparked the growth of ALSPs and new ways to deliver and procure legal services – without the Act the ability of corporate legal teams to instruct a range of diverse suppliers, not just traditional law firms, would not have been possible.

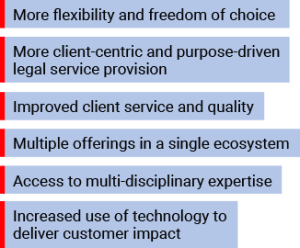

“What it’s done has brought diversity to the market in a way that didn’t exist before. And like all forms of diversity, that brings benefits because it allows different business models to evolve and much more flexibility and freedom of choice.”

__

Helen Lamprell, general counsel

Chris Fowler, former general counsel at BT’s technology division, echoes this sentiment. “The real big thing for me was that it just created a whole market in the UK of different sets of providers, all offering different things at different levels within one ecosystem.”

“Because ALSPs are very good at account management, service delivery, process definition, diversifying, landing and expanding, BT spend with ALSPs has consistently grown.”

This arguably points to another effect of liberalisation: the start of a paradigm-shifting journey in which legal departments actively embrace and advocate for more client-centric and purpose-driven legal service provision, leveraging both their own and industry multi-disciplinary expertise and technology to deliver customer impact.

Benefits of Liberalisation for Legal Teams:

A Value-Driven Approach

Liberalisation has not put the pressure on fees that had been hoped, because demand has kept growing, according to Arlene Adams, the founder of Peppermint Technology. But it has lifted the standard of service she explains: “We’re seeing business customers demanding more value for money and tailored services.”

Speaking to Crafty Counsel on ‘What will an ALSP do for your legal team’, Natalie Salunke at Zilch explains that the agile mentality that ALSPs embrace reflects how she delivers legal services to the companies she has worked for. It also reflects with the way in which those companies provide services to their customers.

She highlights that ALSPs hire employees with diverse expertise, that go beyond technical legal expertise. They are client focused and look for the best solutions for a particular client, as opposed to offering a generic service that has been delivered in the same way to multiple clients before.

Chris Fowler says: “So how are you going to manage that piece of work? How are you going to do things differently? The alternative providers have been very good at helping big organisations with that conundrum because they offer certainty of price.”

“In the old days, if you lost someone or you were a bit short, you either had to go to a law firm or you would get a secondment in. Most in-house functions are now spoilt for choice thanks to alternative providers. What it forces you to do is think about what’s really core and what’s something that you can buy in resource for.”

__

Chris Fowler, former general counsel, BT technology division

ALSPs

hire employees with diverse skills,

that go beyond technical legal expertise

ALSPs

embrace an agile mentality,

which reflects how companies provide services to their customers

Chris Grant, Head of Legal Market Engagement at HSBC, agrees. “That’s a great place to be in because you can then start to evaluate where the best place is to send work from a risk or a pure cost perspective. For some of the work, it is still law firms; but for other work, it is an ALSP that can start to step in.”

On a practical level, another way of achieving more for less has been via flexible resourcing, which can also allow legal teams to run projects in a more cohesive way, explains Helen Lamprell. The added benefit is that it creates a bit more tension in the system for the big law firms, meaning they have to stay on their toes and not get complacent.

And the benefits do not stop there. Chris Grant highlights that once they secure work, ALSPs start looking at how they can do it more effectively and more efficiently, a focus not shared by traditional practices.

Especially in current uncertain economic times – much like that faced by organisations in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis – businesses must consider whether they are spending too much on what they want to achieve.

The aim ultimately is to support lawyers to achieve their goals and for Dana, ALSPs are best placed to suggest fresh or innovative ideas on how the work can be done because many were born out of a sense of disillusionment with the way traditional firms were structured and providing services.

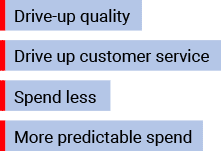

According to Crispin Passmore, the opportunity created by liberalisation is clear: “They [legal teams] can take a much more value-based approach to it where they try and drive-up quality, drive-up customer service, while spending less and more predictably.”. For him, the crux is that more in-house counsel needs to be “much braver” in how they buy and deliver legal services.

Benefits of a value-based approach:

Outsourcing market drivers include:

- Greater emphasis from the business for legal to support differentiating customer experience

- Heightened demands on legal teams alongside tighter budgets

- Growing governance reporting requirements and regulatory change

- Requirement for employed lawyers to deliver on more complex, strategic internal projects

- Wider remit of general counsel within organisations

- Increased pace of business driven by technology advances and market pressures

- Businesses increasingly expect service delivery akin to other organisational departments

A Business Perspective

Most ascribe the fact that there has not been even more change since the introduction of ABSs to the culture in the legal sector. “It’s lawyers and law firms still not thinking like businesses truly would in a market that is still ripe for innovation, development and expansion,” says Stephen Mayson

Arlene Adams has had a front-row seat throughout this period of change. “Certainly, at the top end and the upper mid-market, firms are starting to operate much more commercially and take longer-term views and make longer-term investments, with professionally qualified people in their expertise to run the business, as opposed to legal experts who traditionally did both.”

For a few in-house lawyers, this has been less of a problem. Chris Fowler is one of the few with direct experience of ABSs. The telecoms giant obtained an ABS licence in 2013 and BT Law used an in-house team of over 70 legal and support staff to provide services to external clients, particularly those with large vehicle fleets. It disposed of BT Law to DWF in 2019.

There have been precious few other examples of other large businesses taking advantage of the ability to own law firms. Where it has happened is in local government, often with councils joining forces to spin their legal teams into standalone law firms and, in addition to handling their own work, compete for instructions from other public authorities. At a time of extremely tight finances, the idea of turning a cost centre into a profit centre is very attractive.

Crispin Passmore suggests those in commerce and industry could be similarly imaginative: “The GC of a big company could float off their legal services in partnership with an alternative provider as a joint venture not only to meet their own needs but to compete for work elsewhere.”

Entrepreneur Karl Chapman, now CEO of Kim Technologies, was one of the first people from outside the legal profession to see the opportunities that the Act presented, launching Riverview Law as an ABS in 2012. Its business model quickly evolved to focus on fixed-price managed services for in-house teams and, such was its success, it was bought by EY in 2018.

He reckons that, if the law worked like other industries and sectors, the pace of change “would have been much faster”. But the direction of travel is “inevitable”. Like any other sector, “it will start using the best of people, technology and process to deliver value, serve customers, and so on”.

This sentiment is echoed by Dana Denis-Smith. When budgets are placed under greater pressure as work demands increase – having the choice to select legal service providers, that have both the advantage of thinking as businesses do, and take into account the wider business demands within which the legal function operates – is beneficial.

“A business approach is helpful because it recognises that there is an overarching business budget and the legal budget forms part of that. Once an ALSP understands how the business is structured, solutions – including legal services – can be designed around the challenges the business faces.”

__

Dana Denis-Smith

CEO and founder, Obelisk Support

Multi-disciplinary Expertise

There has been well-documented growth with legal teams of legal operations specialists, legal engineers, design thinking experts and data analysts to name a few.

One impact of this transformation according to Jenifer Swallow, a former general counsel, then head of LawtechUK and now a business and legal consultant to high-growth companies, is that, “the sophistication of the in-house environment has made them a more sophisticated buyer, so the way that they are now thinking about procuring legal services is changing, and changing at a faster rate than before.”

Where swathes of work have been traditionally given to law firms, there is more scrutiny around whether there is an alternative way to do the work, for better value and in a more efficient way.

For Jenifer, the central problem remains the way law firms are incentivised and the focus on maximising billing revenues short term – whereas ALSPs and ABSs have had to be so much more focused on aligning with what their clients want.

When running a legal department like a business in its own right – something GCs are increasingly needing to do – “general counsel realise that certain things don’t make sense, that you need to procure and think about legal services in a different way. That then means you have to shop around and the ALSPs, as well as tech solutions, are a really obvious option”.

This has led law firms to try and offer a wider range of services. Flexible resourcing was the first wave of initiatives, followed by technology solutions and complementary services. This is similarly infusing law firms with people who have different, more commercial mindsets.

DWF, the first law firm to list on the main London Stock Exchange, has arguably embraced this the most. It is now divided into three divisions: legal advisory, connected services – a range of legal and non-legal offerings, such as advocacy, claims management, forensic accountancy and legal costs – and Mindcrest, an ALSP that offers managed services, which it bought in 2020 for £14m.

Nonetheless, Karl Chapman observes how “although not impossible, it is very hard, structurally, to operate a new business model inside a law firm”. He explains: “Take a managed service – fixed-price business with lower margins and a long-term annuity stream – against an hourly billing, transactional model where the risk is with the client and the margins are very high. It’s difficult to accommodate those two models in a single organisation, given the way people are rewarded – by the number of hours billed.”

The firms that can do this are the exceptions, says Chris Fowler. The problem among law firms is that most still look at alternative solutions as just offering up bodies and cannibalising their own work.

A multi-disciplinary landscape

Technology as a Disruptor

Legal technology has proliferated during the past 15 years. Yet Mark Cohen, a lawyer who is one of the leading voices for innovation in the US, highlights that legal tech has become an end unto itself for many ‘legal techies’ – despite ‘plug and play’ solutions becoming more common, and artificial intelligence finding its way into the legal space, the legal function lags business and other professional services in tech utilisation, budget and understanding that tech is an enabler of change.

In his opinion, technology advancement, alongside legal operations, has focused on good delivery hygiene, driving efficiency and profit preservation. To have real impact, fit-for-purpose tech investment and design should be part of a larger strategic plan whose end game is to create new, customer-centric delivery models enabled by technology.

Arlene Adams has the different perspective of someone trying to bring about change to the profession with a Microsoft-first approach to technology via the Cloud. One challenge she recognised early on was the danger of diminishing returns, where law firms had so much tech, it made them unproductive.

“My vision was that firms needed to embrace more of a platform approach rather than trying to manage too many applications in their businesses” .

__

Arlene Adams, founder of Peppermint Technology

Ms Adams explains that she thought at the start of the legal tech explosion it would take five or six years for the message to hit home but feels it is only since the pandemic that she has really started seeing the industry and business owners wake up to it – highlighting that she underestimated how hard it would be to disentangle firms from their legacy systems and the approach of buying legal-specific systems from legal-specific suppliers.

On the other hand, technology is at the core of many of the independent ALSPs’ business models. In addition to leveraging their technology solutions, law firms and corporations are increasingly turning to them as consultants on legal technology, accessing their expertise and experience.

Christina Blacklaws suggests that, ultimately, it will be technology, rather than business structures, that will be the true disruptor of the market by enabling “a totally different way of delivering services”. And the services that are needed, she continues, are those that prevent, rather than solve, legal problems.

“As soon as something disruptive and good comes along at scale, general counsel may desert their long-term providers very quickly and understandably so. Law firms need to be having grown-up conversations with their clients on how to price and what to price for, and how they are going to be incentivised themselves to do things differently.”

__

Christina Blacklaws

Consultant, former Law Society President

UK Lawtech Investment

£674m

UK Lawtech Potential

£2.2bn

Purpose-Driven

Business is well along its paradigm-shifting journey to a customer-centric model explains Mark Cohen. In an article earlier this year for Forbes, New Law?’ You ain’t seen nothin’ yet, he explains that business is also “recasting the purpose of a corporation and redefining its role in a digital world.

He says: “The narrow corporate focus on profit and shareholder value has expanded to a wider stakeholder group. This includes its workforce, supply chain, customers, communities it touches, society and the environment. Corporations have also committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion – not just for themselves but also for their supply chain with whom they expect cultural alignment. The legal function will make this transformation, not only because business demands it but also because it’s good for business.”

Helen Lamprell agrees. AVEVA, like many companies now, want to use suppliers that are diverse and “reflect our values in that regard”. She continues: “We look first at ourselves and whether we are doing the right thing. Then you look down your supply chain and the extent to which it reflects your values. There’s been quite a big step up by everybody in the sector, but firms like Obelisk have been right at the forefront of pushing it and giving women an alternative career path that might have been closed to them before.”

The likes of Obelisk “give people more flexibility in their career choices, so you don’t get quite so many people dropping out of the workforce. And it often provides people with good routes back in. They keep a more diverse group of people in the workforce and that’s a very, very big strength.”

And the commercial benefits for legal teams are evident, as Chris Grant points out. For him, flexible resourcing is exciting for companies because “it taps into a new group of people that we maybe didn’t have access to before”. He adds: “So, it’s changing the bench, which is good.”

For Dana, creating Obelisk Support was also born out of a sense of personal purpose to champion equality for women in the workplace and to provide equal opportunities for women in law.

Questions around diversity and inclusion and who gets to do the legal work and gets to be in the room are important to her and were the driving force for starting her own legal service provider. It is critical to her that Obelisk Support does not merely talk about diversity and inclusion but shows how it is done.

“Having a workforce that is representative of the community at large and of the in-house legal teams helps the ALSP align with the customer and is vital for its ultimate success. With a diverse workforce comes diversity of thought and helps ALSPs solve problems in creative and innovative ways.”

__

Dana Denis-Smith, CEO and founder, Obelisk Support

What does the Future Hold?

Stephen Mayson points to both the Act and the SRA’s interpretation of it – particularly in the early years – as being too prescriptive and acting as a drag.

The more regulators can do structurally, “then the more you can change culture”, Crispin Passmore agrees. Few lawyers realised they could do an awful lot outside of regulation before the Legal Services Act. “So structural change can change attitudes and culture beyond its immediate impact. We’ve got too many regulators and we’ve still got too much regulation. We don’t really need to regulate most of the reserved activities. We could regulate handling money linked to legal transactions, litigation and advocacy, and what else do we really need to do?”

Such radical reform is not on the horizon. So, to harness the full opportunities of the liberalisation to date, Arlene Adams echoes many industry leaders in suggesting that “the biggest legacy issue is mindset”.

A Mindset Change

First and foremost, the culture is changing and needs to change both in-house and in their external advisers, says Jenifer Swallow. It is too easy for general counsel and senior executives to take comfort from instructing a well-known law firm, “even though that may be unnecessary, way overpriced and not structured in a way that aligns everyone’s interests”.

Christina Blacklaws suggests that one of the reasons for this is that a lot of in-house counsel have come from those big City firms. Then they go in-house and “don’t have the bandwidth in their own teams to invest in the analysis needed to do things differently – even though there are cheaper, quicker and more accurate solutions out there that are technologically based and could be transformative for them”.

Crispin Passmore says general counsel can too easily default to instructing the firm they trained at. But this is the model that City law firms have developed. As he bluntly puts it: “Recruit a bunch of lawyers, work a few to death, work a few to partnership and work a few into in-house.” However, as in-house teams start to train their own lawyers, along with some ALSPs and the Big Four, this is going to start to change.

Still, Chris Grant is not surprised that lawyers have been slow to innovate. “Everybody’s trained to do things in specific ways, so you don’t really ever have the opportunity or the thought to do something differently.”

In his opinion, an education process leading to behaviour change is still needed among the in-house community, led by the leadership teams that are, arguably, made up of those most resistant to change. “Do they know the options they’ve got available to them? They know the law firms – they’ve been working with them for a long time. So, we’ve got a job internally to be able to identify which lever can be pulled for what type of activity that we’re trying to do.”

Karl Chapman agrees that, as well as cultural resistance, general counsel have always had the opportunity to drive change. “They hold the purse strings, but they choose to spend their money in traditional ways. They’ve been tremendously resistant to looking at alternatives. This is changing because the pressure is increasingly being put on the corporate legal function, plus there are maturing alternative delivery models, high-quality suppliers and proven technology solutions.”

This is also not a profession of risk takers. But SRA Innovate – through which the regulator will talk through ideas – and LawtechUK’s sandbox, supported by a regulatory response unit made up of various regulators – are starting to change that by offering ‘safe spaces’ to test concepts and have novel conversations.

mindset

Embracing a change in culture will drive change

A True Partnership

The flip side of having all more choice can be that a legal teams end up with multiple different suppliers to manage. This can be a problem, Helen Lamprell acknowledges. At the time of speaking, she was going through the process of identifying how many law firms AVEVA instructed and had reached 62, which may seem a lot at face value, but the company does operate in more than 100 countries.

Key for legal teams to navigate quality control with more diverse supply chains is to establish true partnerships.

The overall picture from the latest Thomson Reuters report on the ALSP market is an industry which has reached a point of maturity, “showing how ALSPs are moving from a simple cost-saving proposition to a true partner than can be counted on for expertise, tech-enabled solutions, and new ways of doing business”.

Natalie Salunke explains that working with an ALSP is an opportunity for the provider to really get to know the business, to become partners and grow together. Investing in a relationship with an ALSP could serve the legal team in the long run as the ALSP can evolve its services to match the needs of the in-house team as it scales.

Helen Lamprell explains that “most importantly, people give good advice when they really understand your business. And that means you want a smaller number of providers who understand you and your needs, unless it’s very basic transactional work, in which case almost anybody can do it. But if you want to go up the value chain to any degree, you want people, even if they don’t work for you all the time, who are familiar with you and know your risk appetite.”

True partnership

Investing in relationships benefits legal teams

The Push for Collaboration

Collaboration is essential to surviving and thriving in the digital age, says Mark Cohen who identifies it as one of the defining characteristics for the future of ‘New Law’.

“The speed, complexity and fluidity of business, the accelerating pace of change, and significant global challenges that cannot be mastered by a single person, function, enterprise stakeholder group or nation demands it.

“The legal function can – and sometimes has – played an important role in the broader collaborative process, pharmaceutical company collaboration in the research and development of the Covid-19 vaccine being a notable example.”

Christina Blacklaws emphasises the importance of collaboration too. She explains how she saw first-hand at the Co-op the benefits of working with “a whole range of different experts and the value that they could bring to the business of law”.

Alongside witnessing the legal function being internally integrated and working cross-functionally with other enterprise business units, Arlene Adams highlights that similarly within law firms collaboration between the different departments needs to be more customer focused, which starts to create a more strategic, rather than transactional, relationship.

And the benefits of collaboration extend across the legal industry too. The Thomson Reuters report also reveals an increasing sense of collaboration, rather than competition between law firms and independent ALSPs (‘co-opetition’, as it’s known). In prior years, corporations would be the ones mandating the use of an ALSP. Now law firms may be the ones bringing that idea forward.

Collaboration

Collaboration is essential for thriving in the digital age

Data Sharing and Standardisation

The legal industry is sitting on a goldmine of data that can enhance its internal performance as well as positively impact the enterprise and its customers observes Mark Cohen.

An ability to harness and share data throughout a business, will enable the legal function to be more proactive in identifying, mitigating and even eradicating risk. It will also help the legal team identify and capture opportunities – driving significant value to the business and its customers he predicts.

In addition, he recommends looking to other industries and how they have benefited from standardisation – despite it being an anathema to many lawyers as it undermines the myths of legal exceptionalism and bespoke legal work. For them, it is a way to share investment costs, increase speed to market, simplify processes and create uniform quality standards.

Data

Data sharing and standardisation will positively impact legal teams

In Conclusion

The past decade of liberalisation in England and Wales has been exciting. Notwithstanding the perception of lawyers as traditional and risk averse, an increasing number have unleashed their entrepreneurial spirit to reimagine how legal businesses are structured and deliver their services.

This new breed of legal business appreciates its staff and the importance of their wellbeing. It builds services that are genuinely client-centric. And it makes choice real – the idea that all law firms are pretty much the same no longer holds true.

ALSPs are an increasingly prominent feature of this landscape, enabling supply chain diversity to drive up quality and customer service while making costs more predictable and manageable. They are also helping to force a much-needed change in mindset, alongside advances in the use of technology and data. Evolution of the market is only going to accelerate from here as a value-based approach to legal services takes a firm hold.

More fundamentally, making legal services delivery more diverse and inclusive means we are seeing the development of a more inclusive, values-driven and purpose-led legal profession. And that can only be good for everyone, especially given the pressures inherent to the kind of economic downturn we are now facing.